AEG Turbine Factory

More than a monument

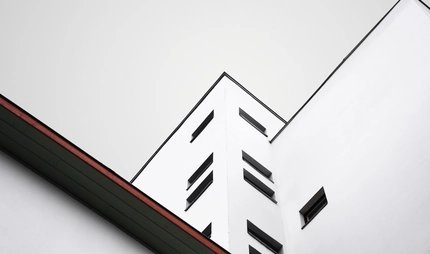

You will find one of the pivotal moments in architectural history set in stone on Huttenstraße in the district of Moabit.

The AEG turbine factory is a turning point in architectural history: architect Peter Behrens and engineer Karl Bernhard were the first to apply stylistic elements to an industrial building. However, instead of just using stone and chisels, the creators used more modern materials for the turbine factory: glass and steel.

But let’s begin before the turbine factory became a legend. Just after the turn of the century, the Berlin electricity company AEG (Allgemeine Elektricitäts-Gesellschaft) started producing steam turbines and therefore needed new factory capacity. Steam turbines were more effective than conventional steam engines and were in demand all over the world.

The invention of modern industrial architecture

The contract was awarded to Peter Behrens, who had studied at schools of art in Hamburg, Karlsruhe, and Düsseldorf. Working as a designer and architect, he developed a corporate design for AEG before anyone had ever used the term, creating product designs, fonts, and the AEG company logo.

At the Darmstadt Artists' Colony, he had caused a stir as an architect with the Haus Behrens in 1901 and co-founded the Werkbund in 1907. This was where companies such as AEG came together with politicians and artists to promote the development of high-quality and modern products. While the Werkbund’s initial focus was on applied arts, architecture also became increasingly important later on.

Behrens was given a unique opportunity in 1908 with the design for the new AEG turbine factory. Never before had anyone attempted to develop a dedicated architectural style for factory buildings. Previously, in line with the prevailing artistic taste of the German Empire, architects had designed historicising façades for industrial buildings.

Behrens’ turbine factory was a prototype. A steel skeleton supported the building and the façades were filled with glass, making the hall appear bright and transparent. Natural light was supposed to increase labour productivity and – as Walter Gropius put it – motivate workers to participate “more joyously in the achievement of great common goals”.

Sacral allusion meets pure functionalism

On its completion in 1909, the turbine factory was considered extremely modern. But if you first take a look at the façade from the front, you will see that Behrens and AEG did not completely renounce the tastes of the times. The concrete elements on the left and right are reminiscent of an Egyptian temple. Although distinctly weighty, they have no load-bearing function as they are only exterior cladding and purely for show. Contemporaries understood the sacral allusion and referred to it as the “machine cathedral”.

The side façade of the turbine factory on Berlichingenstraße, however, is completely different and extremely modern. The construction hides nothing, enabling you to see the steel girders and their joints. The glass façade tilts slightly inwards as it follows the pillars, which appealed to the chief construction engineer, Karl Bernhard, and observers can see the actual façade.

Karl Bernhard remains underrated to this day. He not only executed Behrens’s ingenious design, but was also heavily involved in it. However, when it came to AEG’s public image and public perception, the focus remained on Peter Behrens: the famous artist-cum-architect overshadowed the engineer.

Visible purpose

Regardless who contributed more to the design, the impact of the turbine factory on architectural history cannot be overstated. It gave industrial production a characteristic element of style. It didn’t hide behind pseudo-historical façades but enabled its functions to be seen by all.

The later Bauhaus architects Walter Gropius and Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, as well as Le Corbusier also worked in Behrens’s office. Mies van der Rohe even worked on the design for the side hall of the AEG turbine factory.

The AEG turbine factory survived the Second World War – even with a larger floor plan, after AEG extended the hall to the north in the 1930s. Since Siemens took over the premises in 1977, all that remains of AEG is the brand name. However, Siemens still produces gas turbines in the hall to this day – a new generation of the 1909 product. Even if the technology has constantly evolved, the name of the turbine factory still remains apt.

Our tips on the Huttenstraße location

Moabit today is still characterised by production and residential areas. In addition to the existing industrial sites, the district contains important testimonies to Berlin's industrial culture. Typical examples include the 19th century Arminiusmarkthalle. Initially established to supply the locals with basic provisions, today you will mainly find regional food, design products and services from creative businesses. The Carl Bolle dairy, which was founded in 1879 and was Berlin’s largest and best-known dairy company, now mainly houses service providers. The site is openly accessible and you can stroll along the river Spree or visit the Patio restaurant ship. Both locations are easy to reach by the TXL bus that runs between Tegel Airport and Berlin’s central station (Hauptbahnhof).

Practical information from visitBerlin

To get to the AEG turbine factory from Hauptbahnhof, take the TXL bus going to Tegel airport and get off at Beusselstraße. We recommend the Berlin Welcome Card for exploring the city by public transport.